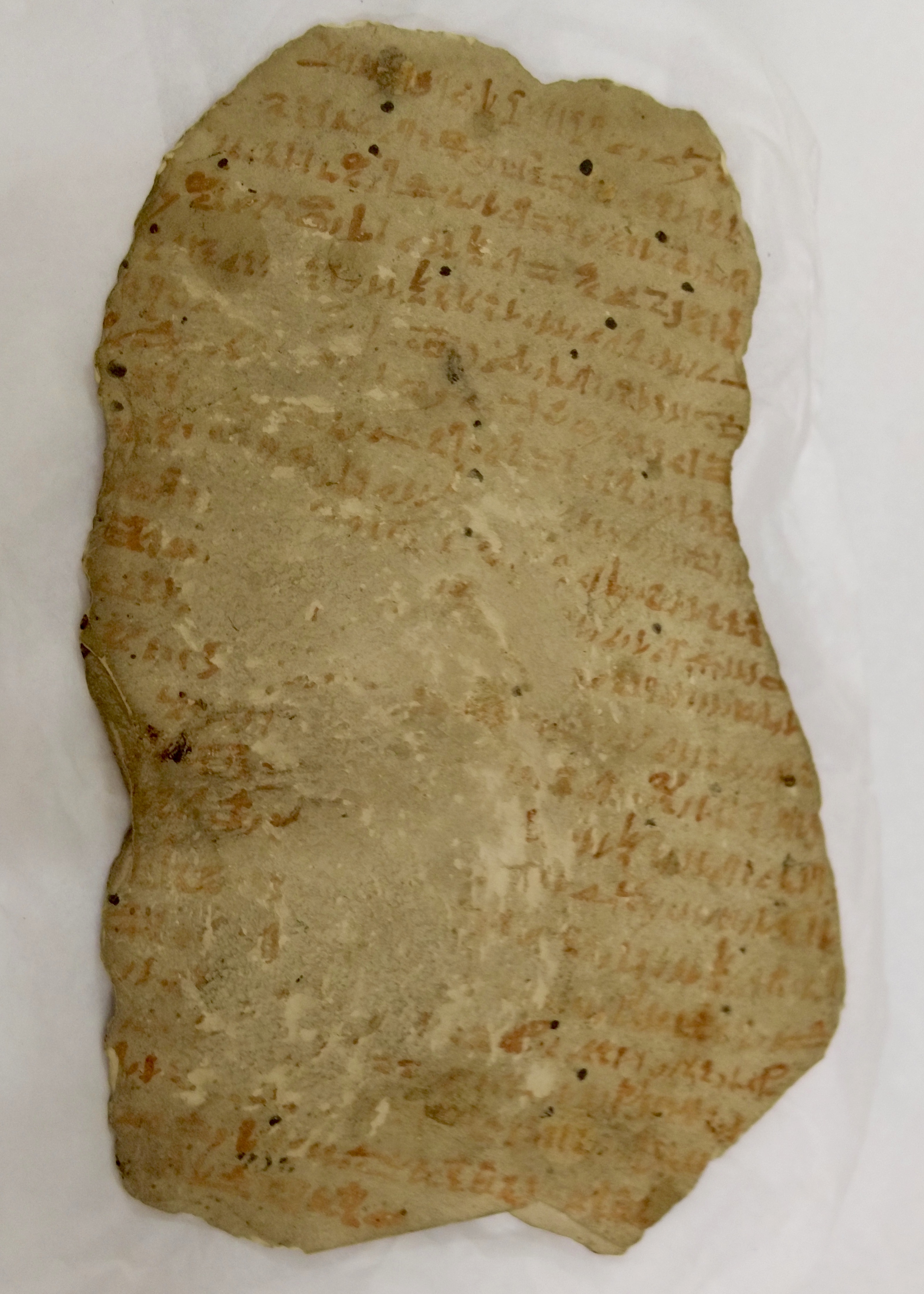

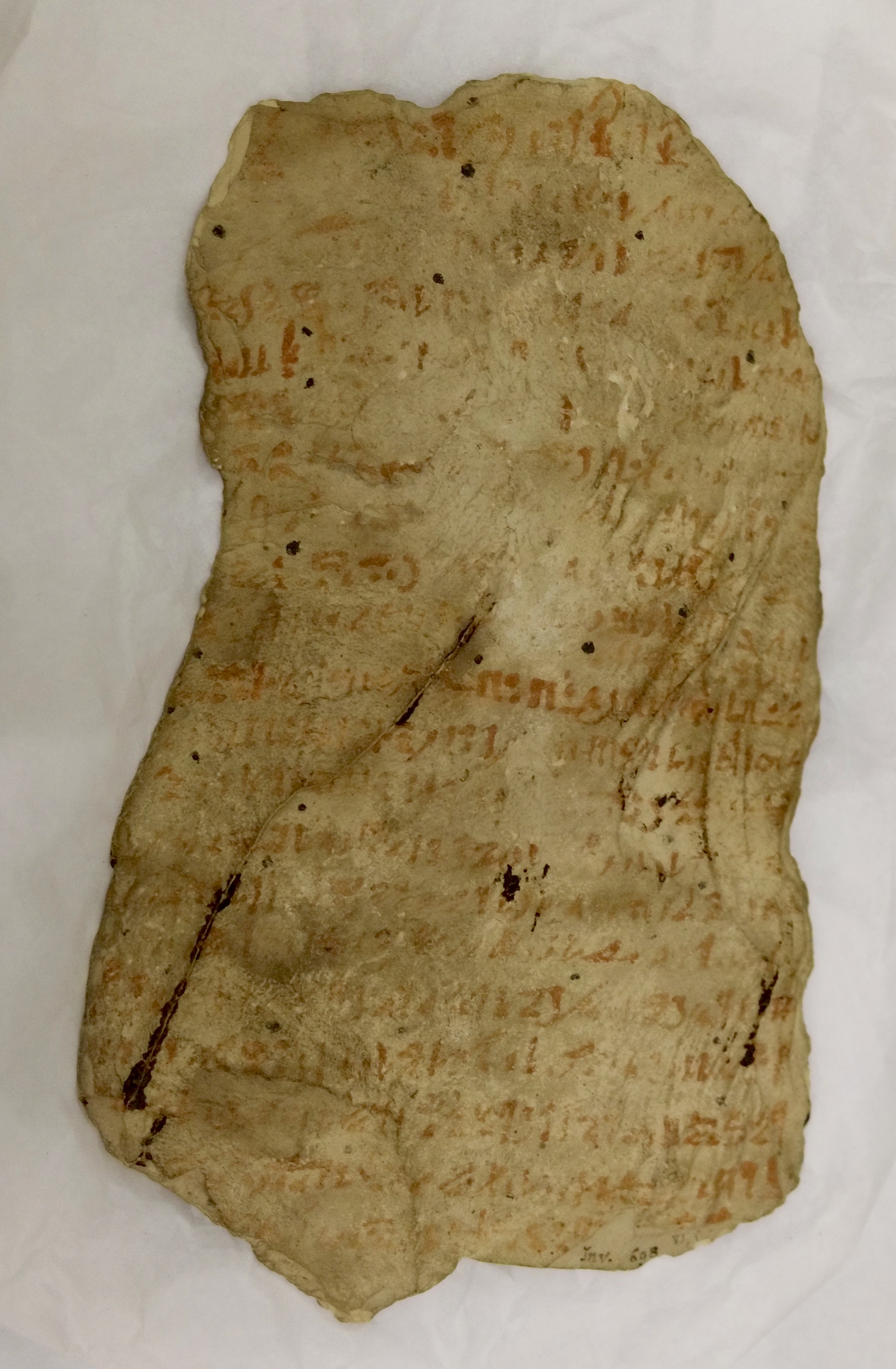

Underneath the Louvre in Paris, in the museum’s cavernous archives, there’s a chunk of limestone almost exactly the size of a human hand. Known as Ostracon Louvre N 698, it is one of ancient Egypt’s many Letters to the Dead, but it is unusual in several ways. First of all, it is rather spectacularly written in red ink, with annotations in black, the opposite of the usual approach. It is the largest letter of its kind, and, the last known. And, uniquely in what has been discovered so far, it is not a letter to a dead person, but rather to the coffin of a dead person, Butehamun’s letter to the coffin of his dead wife Ikhtay.

Sadly, its provenance is unclear. It was already in the Louvre’s collection when the first catalog was compiled in 1857. It was probably obtained from one of the notorious antiquities “collectors”, like Bernadino Drovetti or Henry Salt.

The letter would have been placed close to Itkhay’s coffin, but the tomb itself has been lost. Commenting on the ostracon, Deir el-Medina expert Jaroslav Černý writes: “Unfortunately many lines are irretrievably damaged by the rubbing to which the stone was exposed after it had been thrown out of the tomb by impious hands into the rubble of the Theban necropolis”.

The ostracon is an example of a Letter to the Dead. Ancient Egyptians believed in an afterlife, and the ability to communicate with the dead. Generally, the goal was to get the deceased to intercede in connection with some kind of unfortunate situation experienced by the letter writer. Often the deceased was believed to be the source of the problem. Letters to a deceased person were often written on papyrus and placed in a bowl at the tomb. (Answers came in dreams.)

There are around 15 letters in the genre, and Butehamun’s written in the same hand as his Late Ramesside Letters.

The text itself is difficult, and translation in some places uncertain. Orly Goldwasser contrasts it with the bureaucratic tone of Butehamun’s other letters, saying that with its red writing and verse points in black as found in literary texts it has a ‘superior style bordering on poetry’.

Most of what can be read of the letter is typical for the genre, but a number of lines stand out. P.J. Frandsen comments on the line:

‘Send the message and say to her, since you (ie the coffin) are close to her: “How are you doing? How are you?” It is you who shall say to her: “Woe (you) are not sound”, so says your brother, your companion, “Woe gracious faced one”…’

Frandsen asks if it is possible that this reflects a lack of communication between Butehamun and his wife that could be due to some shortcoming on his part? Alternatively, he suggests that the scribe’s alleged polygamy might be involved.

Perhaps more interesting in light of the reburial project is the final section of the letter, which reads (in Orly Goldwasser’s translation, italics mine):

‘Statement by the necropolis scribe Butehamun to the chantress of Amon Ikhtay: “Pre has departed, his Ennead following him, the king as well.

All humans in one body following their fellow-beings.

There is no one who will stay,

We shall all follow you;

Can anyone hear me in the place where you are?

Tell the lord of eternity, Let my brother arrive.

Make—-

Their great ones as their small ones.

It is you who will tell good tidings in the necropolis,

Since I committed no abomination against you while you were on earth;

So grasp my situation,

Swear to god in every manner,

Saying: “It is in accordance with what I have said that things shall be done”.

May I not deceive your heart in anything I have said; Until I reach you.

–in every good manner. Can anybody hear at all?”’

This passage seems to indicate that Butehamun is having a crisis of faith, in his belief in the afterlife or whether the gods listen. Goldwasser says the phrase ‘does anybody hear?’ is ‘a unique sceptic contemplation, very rare the Egyptian literature’. Frandsen writes:

‘The open skepticism of this passage towards the prevailing view, in the second millennium, of the “ultimate reality” may be seen as a forerunner of the much more pronounced tendency known from documents of a later period.’

Unless further texts turn up, it is impossible to know what led Butehamun to question the afterlife, if that is what this is.

The significance of the unique measure of communicating through the coffin as an intermediary, is difficult to evaluate but it may underline the importance to Butehamun of the coffin in the afterlife, which in turn might point to the importance to him of his own coffin and its imagery.

(Many thanks to the Louvre for granting permission to use the images of Ostracon Louvre N 698 online.)

The Caches The Remorse of Butehamun