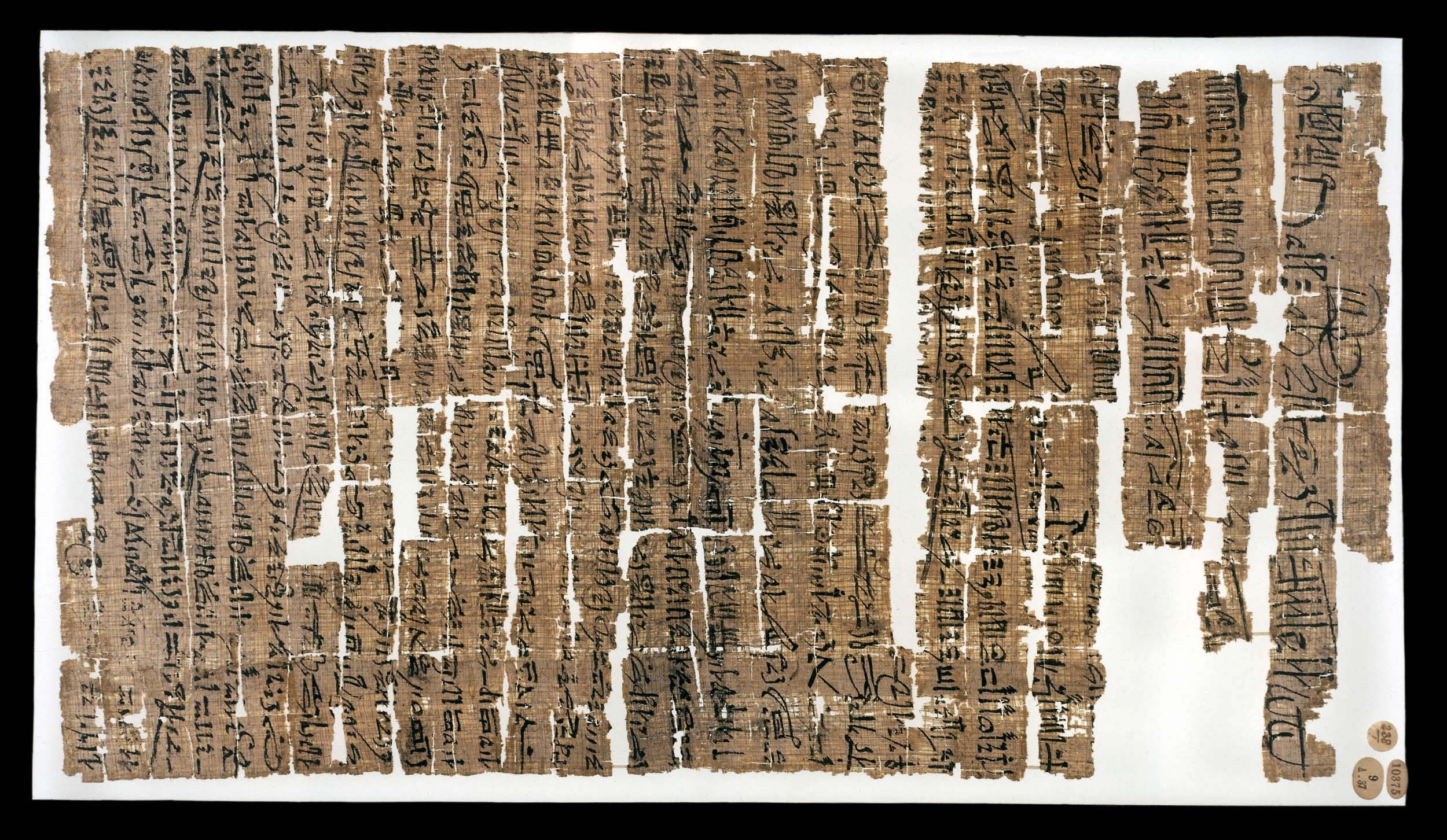

LRL 28, Papyrus British Museum 10375, written by Butehamun possibly acknowledging the reburial project. Photo: ©Trustees of the British Museum

During the 19th and 20th Dynasties the capital of Egypt had moved from Thebes to the north, however the kings continued to be buried in the Valley of the Kings. But while a tomb was begun there for the final king of the 20th Dynasty, Ramses XI, it was never used by him. After his death the rulers of the new 21st Dynasty began a new custom of burials within the easier-to-protect precincts of a temple in their capital of Tanis.

There was no longer a need for a crew based at Deir el-Medina to create new tombs in Western Thebes. But the rulers of the south, the High Priests of Amun, evolved a new project. With the loss of the Nubian goldmines, their state needed resources. Following the increase in tomb robberies during the 20th dynasty and the depredations of Libyans in the area, old royal mummies were removed from their original tombs, often rewrapped, and moved to hidden caches. In the process of rewrapping, those carrying out the scheme removed the gold, jewels, and amulets from the mummies, along with anything else considered of value in the tombs. Some have called this process preservation, others plundering, or a combination of the two. In a way it paralleled the dissolution of the monasteries under Henry VIII, in providing new wealth to the state.

The ‘Late Ramesside Letters’ (or LRL) is the name given for around 50 papyri containing personal correspondence mostly to and from the Deir el-Medina community. Their provenance is somewhat ambiguous, although the papyri seem to have been collected by the British consul Henry Salt and others in Luxor in the early 19th Century, and distributed onwards to museums around Europe, from London and Paris to Berlin and Geneva.

Most of the LRL are letters to or from Butehamun or his father Dhutmose. They seem to date from year 12 of Ramses XI to year 12 of the ”Whm-Mswt”.

Many of the letters deal with private issues (for example raising the ambiguous question of the apparent multiple wives of both Dhutmose and Butehamun ). In them one can read of Dhutmose making at least one journey south to Nubia in the company of the general and High Priest of Amun Piankh. Piankh also sends a number of orders to the workers in Deir el-Medina, and it is one of these letters, or rather the answer to it, dated to year 10 of the ”Whm-Mswt”, where we can see what seems to be an assignment as part of the the reburial project.

In LRL 28 Butehamun replies to Piankh:

’Now you have written saying “Uncover a tomb among the ancient tombs, and preserve its seal until I return,” so said he our lord. We are carrying out commissions. We shall enable you to find it fixed up and ready – the place which we know about. But you should send the Necropolis scribe Tjaroy to have him come so that he may look for a marker for us, since we get going and go astray not knowing where to put our feet.’

There are no other obvious references to this project in the LRL, although in LRL 30 (dated by Wente after LRL 28) Piankh writes to Butehamun:

’The scribe of the Necropolis Tjaroy and the troop commander and prophet Shedsuhor have reached me; they have rendered report to me of all that you have done. It is all right, what you have (done), you joining up and doing this work with I charged you you to do and writing me about what you have done.’

This could refer to the reburial project, but it could of course also refer to some other assignment sent by this High Priest and General to Butehamun. The project itself may have already begun, as graffiti in KV 57 (see below) dates from a Year 4 and Seti I underwent a ‘repetition of burial’ in Year 6 of the Whm-Mswt.

The restorers entered the tombs of Seqenerna; Ahmose I; Amenhotep I; Thutmose I, II, and III; Amenhotep II; Thutmose IV; Amenhotep III; Horemheb; Ramses I; Seti I; Ramses II; Merenptah; Seti II; Siptah; Tausret and Setnakht; Ramses III-VI; and Ramses IX. The process also included the restoration and reburial of mummies of several queens and royal children of the 17th and 18th Dynasties. (Possibly because they were regarded as ‘tainted’ by later generations, the tombs of the Amarna royal family were excluded. ) (Unless Fletcher is correct in identifying one of the mummies in KV 35 as Nefertiti. )

Several different kinds of treatment were involved. Notes known as ‘dockets’ were placed on the coffins or in the wrappings, noting the identity of each mummy and sometimes the treatment they had undergone and the personnel involved. In the simplest case, mummies were rewrapped and left in their original tombs. Other treatments included ‘burials’, ‘repetition of burial’ and ‘Osirification’, which seems to have been a rewrapping of the corpse in the form of Osiris.

The wrappings of the mummies were stripped of all valuables. Most of the mummies were left inside anthropoid coffins, which made for easier moving, but also reflects the importance of the coffin for the presumed resurrection of the individual. But many of the coffins were stripped of their gold leaf, replaced with applications of yellow paint.

The funerary equipment, which presumably would have been at least as abundant as in the tomb of Tutankhamun, was also apparently taken by the restorers, leaving behind only items thought to have been of less value, such as shabtis, wooden statues, and canopic jars.

Peden calls ancient Egypt ‘The classic land of graffiti’, commenting that there isn’t such a rich body of texts anywhere else in the Near East or the Mediterranean. Thebes in the New Kingdom and Third Intermediate Period is a trove of graffiti, and Butehamun and his father Dhutmose were among the most prolific writers. Butehamun is referred to by name in more than 100 inscriptions.

While the reasons for the graffiti are usually not indicated, prior to the Whm-Mswt many indicated locations of tombs, possibly so the workmen could avoid breaking into old tombs when they started new ones, as had happened on some occasions. With the Whm-Mswt, much of the graffiti appears to have been in connection with the reburial project, as inscriptions have been found in and around the sites of several of the caches, as well as in connection with tombs from which mummies were removed. A great number of graffiti during the Whm-Mswt record inspections, and the majority carry the names of Dhutmose and/or Butehamun.

What are known as ‘dockets’ are short notes left in association with the mummies that have been rewrapped and moved. There are two types: Type I dockets contain a record of the deceased’s name, often with details of status. Type II include a date, a record of the work undertaken, and the names and titles of the personnel involved. Dockets are found in three places: on the wrappings covering the chest of the mummy (Linen dockets or LD), on the coffin lid (Coffin dockets or CD), or on the walls of the tomb (Wall dockets or WD, which seem to be exactly the same as graffiti).

Remarking on discrepancies between the names on coffins and the dockets on mummies within, some researchers have questioned the veracity of the dockets. Reeves concludes that the reburial personnel didn’t really care what mummy went into what coffin, but were meticulous in getting right name on the mummy (to the extent that if they didn’t know whose mummy it was they didn’t leave a docket). Together with nearby graffiti, the dockets provide insights into the reburial project.

Butehamun seems to have been in charge of the initial stages of this project. A review of the primary sources connected with the scribe reveals aspects of his role in the reburials.

The House of Butehamun The Caches