The question raised by Ostracon Louvre 698 is why was the letter written to a coffin? Does this indicate that the coffin, the vehicle that took a dead person to the afterlife, was particularly important to Butehamun? If so, does Butehamun’s own coffin reveal anything about his feelings about the afterlife, or about the reburial project he led?

Butehamun’s son Ankhefenamun bears the title of “royal scribe” in the year 16 of Smendes (around 1050 BC), by which time Butehamun may have died. The last record of Butehamun is in TT 291, the tomb of Nu and Butehamun’s relative Nakhtmin. While nothing of Butehamun (nor anyone else, except a stela of Nakhtmin) was left to find in this tomb, the wall in a chapel bears the graffiti:

‘Ankhefenamun, son of Butehamun’.

and

‘Thine is the West, ready for thee, all blessed ones are hidden in it, sinners do not enter or any unjust. The scribe Butehamun has landed at it after an old age, his body being sound and intact. Made by the scribe of the tomb Ankhefenamun.’

This might indicate that Butehamun was buried in what would have been the family tomb, presumably emptied by Drovetti or those who worked with him. The Egyptian Museum in Turin lists the provenance of Butehamun’s coffins and other grave goods in their galleries as TT 291, and “Drovetti Collection”.

Interestingly, Butehamun seems to have rejected one coffin in favor of another. His first coffin, never used, was found by Drovetti and Salt’s contemporary Giovanni Belzoni, and is in the Musées royaux d’art et d’histoire in Brussels.

The coffins that Butehamun did use, and some of his grave goods, are on display at the Egyptian Museum in Turin. An early example of a yellow coffin, what makes it exceptional are two of the registers at the lower right, where Butehamun is shown burning incense before Amenhotep I, his mother Ahmose-Nefertari, his sisters Ahmose-Sitamun and Ahmose-Meryatamun, and their relatives from earlier generations Queen Ahhotep and Prince Ahmose-Sapair. All of them were objects of the Reburial Project, and their mummies (or coffin in the case of Queen Ahhotep) all ultimately ended up in the great Royal Cache TT 320.

Butehamun worshipping royals on his coffin lid, C 2236/1, Egyptian Museum in Turin, Photo: George Wood

It is highly unusual, if not unique, for 21st Dynasty coffins to portray images of anyone other than deities. While Amenhotep and Ahmose-Nefertari did have that status, as the patron gods of Deir el-Medina (and portrayed as such on the columns of Butehamun’s house in Medinet Habu), the others did not. But Butehamun seems to have been involved in the removal, rewrapping, and plundering of their mummies.

So what is going on here, why is Butehamun portraying these images on his all-important coffin?

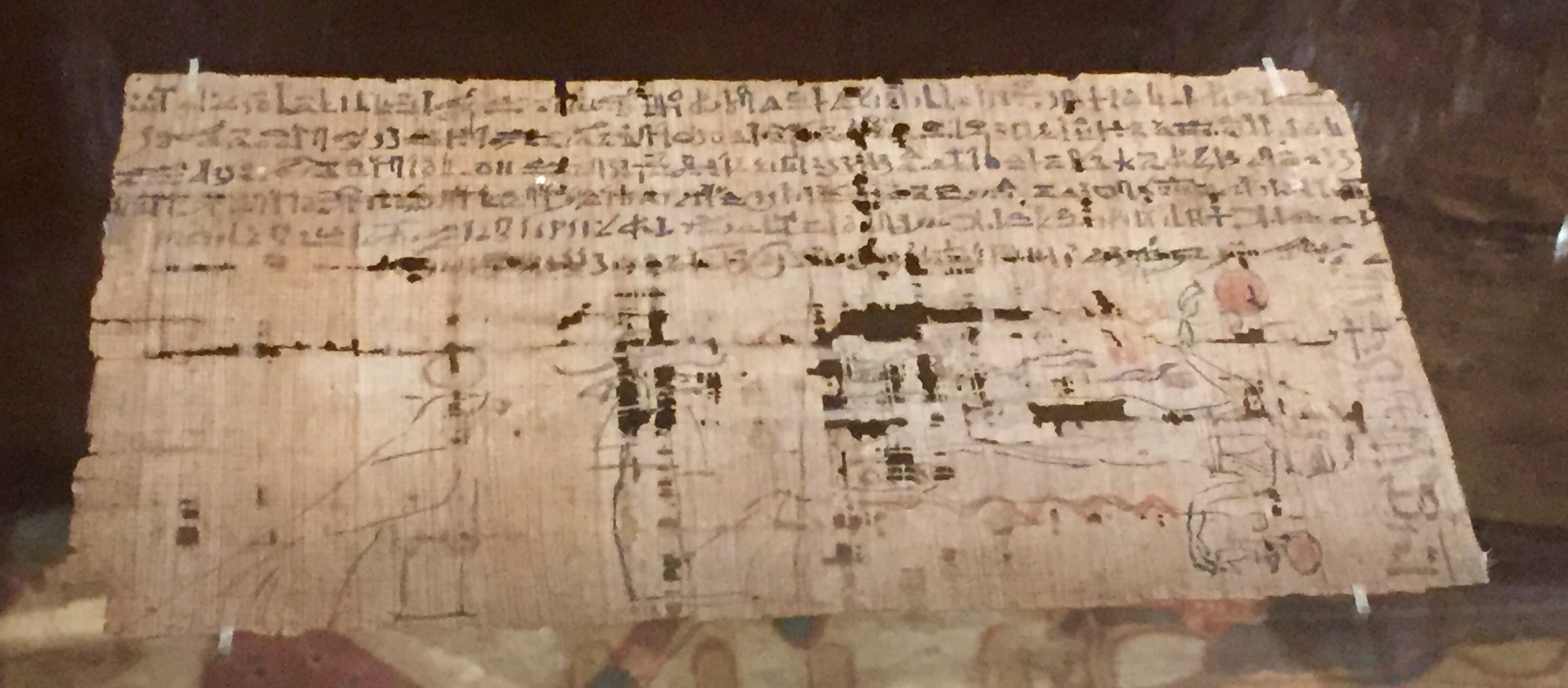

Among the grave goods of Butehamun at the Turin Museum is a small papyrus containing Chapter 10 of the Book of the Dead, a spell to transform the dead person into an “excellent spirit” before entering the boat of Re, which would have been rolled up and used as an amulet.

The “Magical Papyrus” of Butehamun, Chapter 100 of the Book of the Dead, it would have been folded and worn as an amulet, in the Egyptian Museum in Turin, Photo: George Wood

Did Butehamun doubt the afterlife, or at least the interest of the gods in human affairs, as Ostracon 698 seems to indicate? Or, did the images of the patron deities of Deir el-Medina on the columns of his house and on his coffin lid, and the amulet, reflect strong belief? Was Butehamun just playing safe in case the gods really were there, or did a more pious son place the amulet in his coffin?

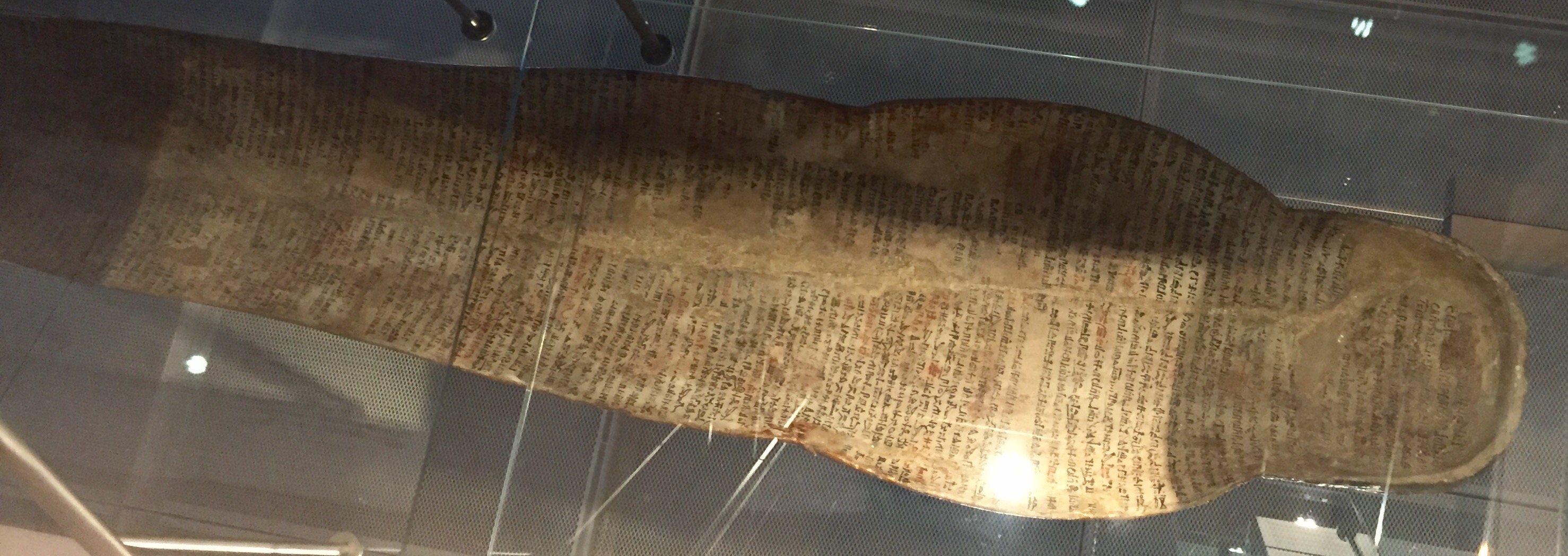

“The Ceremony of the Opening of the Mouth”, part of the funeral ritual, inside the inner coffin of Butehamun, Egyptian Museum in Turin, C 2237/3, Photo: George Wood

Any of these might be reflections that the reburial project had a profound effect on the man who led it. After all, Butehamun, with official sanction, broke into many, many royal tombs, and defiled and robbed the mummies of countless Egyptian kings and other royalty, before he rewrapped them with reverence, carefully labelled them carefully to indicate exactly who they were, and then dumped them into the secret caches in any handy coffin. The lack of apparent retribution might be enough to make anyone doubt the gods. Or it might have led to deep concern and fear for his own afterlife. Unless a new letter from Butehamun appears detailing his thoughts, we can never know what was going on in his mind during and after the project.

Can the unique letter to a coffin and the unprecedented imagery on his own coffin show remorse or anguish for the way Butehamun had treated the royal mummies, perhaps a propiation to the gods and the deceased royals to forestall punishment?

Or, was Butehamun using the coffin imagery to reflect satisfaction with a job well done?